A Case of Intellectual Disability without Epilepsy Associated with a Pathogenic Variant of STXBP1

Article information

Syntaxin-binding protein 1 (STXBP1) is a representative gene related to intractable epilepsy. Pathogenic variants of STXBP1 cause a phenotype of developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 4 [1-4]. Diagnostic tools for pathogenic variants of STXBP1 have recently been developed using genetic tests such as targeted gene panels or whole-exome sequencing [5]. The disease phenotype comprises early-onset seizures, including tonic spasms, a suppression-burst pattern on electroencephalography (EEG), and profoundly impaired intellectual development. Subsequently, most patients progress to intractable epilepsy, such as West syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome [1,2]. Progression to Dravet syndrome, as well as classic or atypical Rett syndrome, has also been reported [1,3]. Various anti-seizure medications (ASMs) have been used to control seizures in patients with STXBP1 mutations, but most become refractory to conventional ASMs [2,4]. However, patients with STXBP1 mutations who have intellectual disabilities in the absence of epilepsy have rarely been reported [6]. This report presents a case of intellectual disability without epilepsy associated with an STXBP1 mutation. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine (3-2017-0168). Informed consent for this retrospective study was waived by the board.

The case concerns a 14-year-old boy with no specific history at birth, but with global developmental delays during childhood. He was unable to walk independently at 12 months and to say “mama” and “dada” until 2 years of age. Brain magnetic resonance imaging findings revealed minimal corpus callosum hypoplasia, and genetic tests for Fragile X syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome were negative. There was no seizure history, and no epileptogenic foci were observed on EEG. In the metabolic work-up, mitochondrial dysfunction was suspected from a urine organic acid test due to the presence of elevated levels of citric acid cycle intermediates such as ethylmalonic acid, succinate, and citrate, and no pathologic findings were found on muscle biopsy. Complex I deficiency was diagnosed in a biochemical analysis. The patient was diagnosed with severe intellectual disability with autistic features and mitochondrial dysfunction; he was administered psychiatric medication along with multiple vitamins, such as vitamin B, vitamin C, ubiquinone, thiamine, and L-carnitine, and received cognitive development therapy.

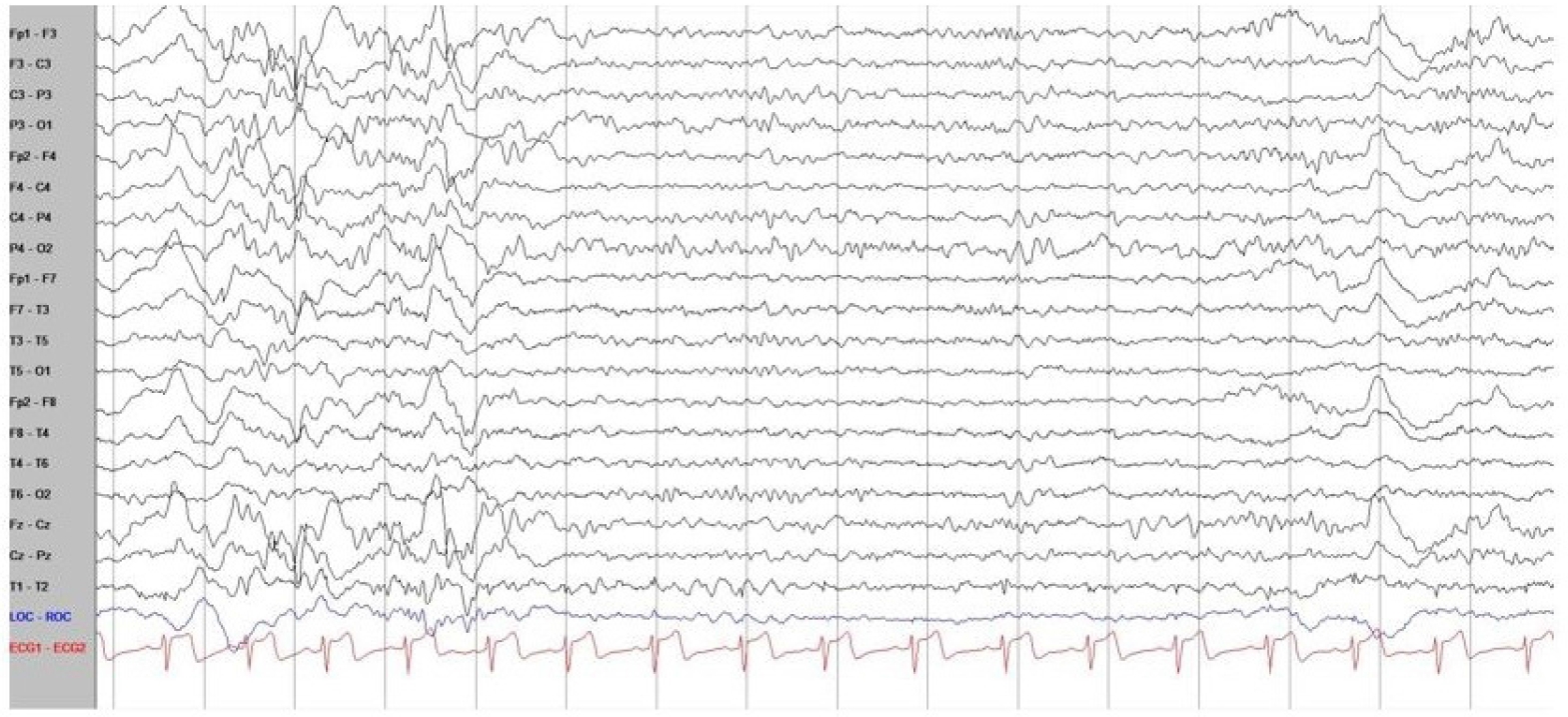

With recent advances in genetic diagnostic tools, next-generation sequencing of the patient’s blood sample revealed a pathogenic variant of STXBP1 (nucleotide NM_003165.3:c.325+2_325+3delTG), which was confirmed as a de novo variant in the Trio test. De novo pathogenic variants of STXBP1 cause early-onset neurocognitive conditions, early infantile epileptic encephalopathy type 4 (EIEE4, also known as STXBP1 encephalopathy), epilepsy, developmental delay, and intellectual disability [7]. The patient recently had symptoms of seizure-like movements, such as vacant staring, brief motion arrests, and involuntary tremor-like behaviors. In a long-term video EEG, none of the abnormal behaviors reported by the parents were associated with epileptic discharges. In addition, no other seizure-related findings or epileptogenic EEG findings were observed. Only slow waves with a disorganized background rhythm were observed, mainly in both frontal areas; this finding was very different from most phenotypes of the pathogenic variant of STXBP1 (Fig. 1). The typical EEG findings of STXBP1 encephalopathy are characterized by focal epileptic activity, burst suppression, hypsarrhythmia, or generalized spike and slow waves. Most pathogenic variants of STXBP1 are accompanied by intractable epilepsy, and the gene was first described in patients with severe epileptic encephalopathy [1,8]. The review by Stamberger et al. [6] indicated that 140 of 147 patients (95%) with STXBP1 mutations had intractable seizures.

Electroencephalography (EEG) of the patient with a pathogenic syntaxin-binding protein 1 (STXBP1) variant. The background of EEG was mildly slow and disorganized mainly in both frontal areas, without any epileptic discharges, and normal sleep tracing was recorded. In addition, there were no seizure-related findings or epileptogenic findings on EEG.

Intractable epilepsy caused by a pathogenic variant of STXBP1 not only has a negative developmental impact on patients, but is also sometimes life-threatening. Therefore, many pediatric neurologists treat seizures by attempting a ketogenic diet, palliative care, or resective surgery, as well as using various ASMs [1,8].

A phenotype in which the STXBP1 mutation is associated with severe intellectual disability, but not associated with epilepsy, has rarely been reported. Hamdan et al. [9] reported the first case of a patient with a truncating mutation in STXBP1 who did not show epilepsy. Gburek-Augustat et al. [10] also reported three female patients with ataxia-tremor-retardation syndromes caused by a de novo STXBP1 mutation. Their reports are similar to the case presented here, showing that the spectrum of STXBP1 presentation can be broad.

As in this case, the STXBP1 pathogenic variant can be diagnosed in cases of intellectual disability, autistic spectrum disorder, ataxia, and dystonia. Therefore, there is a need to consider the STXBP1 pathogenic variant in the differential diagnosis for patients with moderate to severe developmental delay. Early genetic diagnosis and targeted treatment plans will become more important in the future, with further developments in technology. The correlation between various pathogenic variants of STXBP1 and the epilepsy phenotype has not been established, and further studies and observations are needed in the future [1]. The observation of this phenomenon expands the clinical spectrum associated with pathogenic variants of STXBP1, and further genetic functional studies on STXBP1 are needed.

Notes

Young-Mock Lee is an editorial board member of the journal, but he was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: JHN and YML. Data curation: GS and JHN. Methodology: HL and YML. Writing-review & editing: GS, JHN, and YML.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all staff members, doctors, and statistical consultants who were involved in this study.