Pediatric-Onset CLIPPERS: A Case Report and Literature Review

Article information

Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) is a rare neuro-inflammatory disorder with only 10 pediatric cases reported worldwide. The diagnostic criteria proposed in 2017 [1] require clinical criteria (pontocerebellar dysfunction with an exquisite response to steroids, in the absence of peripheral neurological disease and other explainable etiology) and radiological criteria (homogenous gadolinium-enhancing nodules of less than 3 mm, predominantly in the perivascular regions of pons and cerebellum, which resolve with steroid therapy) to be fulfilled for probable CLIPPERS and additional histopathological criteria (lymphocytic, predominantly T-cells, infiltrating perivascular sites) for definite CLIPPERS. In 2019, revised criteria [2] that included a change in the size of the nodules to less than 9 mm, were proposed to improve diagnostic specificity. CLIPPERS has different outcomes between children and adults, as at least 30% of pediatric cases were associated with alternative diagnoses such as familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (fHLH) and 20% had residual severe disabilities [2,3].

We report a case of probable pediatric CLIPPERS with a good outcome in a patient who presented with acute cerebellar signs and classical post-gadolinium brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features of punctate lesions of the hindbrain and responded exquisitely to steroids. He was also screened for fHLH, and no known genetic mutations were detected.

A previously well 10-year-old boy presented with a 1-week history of progressive headache, diplopia, and unsteady gait, with no other neurological or systemic symptoms. There was a history of pancytopenia attributed to viral illness 3 years ago that had self-resolved. On examination, he was afebrile and had a full Glasgow Coma Scale score with appropriate behaviour for his age. He had truncal ataxia and a broad-based gait with past pointing, dysdiadochokinesia, and intentional tremors bilaterally. There was no ophthalmoplegia, fundoscopy showed no optic neuritis or papilledema, all other cranial nerves were intact, and the tone, power, and reflexes of both upper and lower limbs were normal. There was no hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy, and the findings of other systemic examinations were normal.

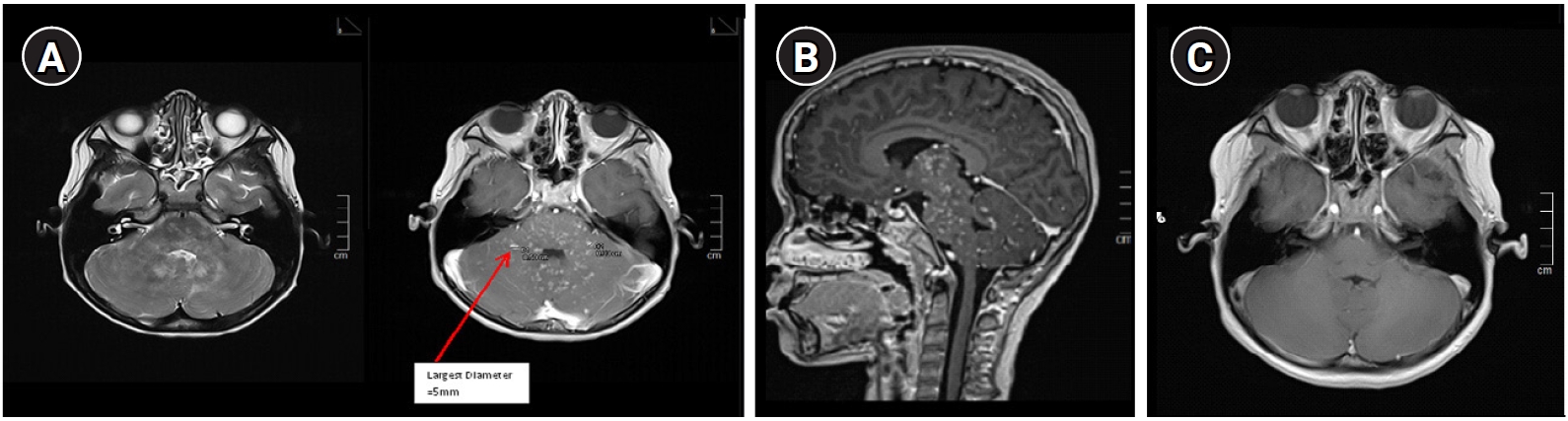

Investigations were conducted with the aim of ruling out infection, posterior circulation stroke, demyelination, or malignancy. His full blood profile had no features of hematological malignancy. Complement levels (C3 and C4) and levels of immunoglobulin G, A, M, and E were within normal limits. Antinuclear antibody and aquaporin-4 antibody were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed a normal protein level of (0.487 g/L), a glucose ratio of 72%, a cell count of 0, and negative culture findings. CSF oligoclonal bands were not detected. Brain computed tomography showed no mass, hemorrhage, or infarcts. Brain MRI with contrast showed signal abnormalities of punctate and curvilinear-pattern enhancement involving the perivascular space in the cerebellum and pons, with cranial and caudal extension on T2 and post-gadolinium images (Fig. 1A and B).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain axial (A) and sagittal section (B) of the hind brain comparing T2w and post-gadolinium images pre-treatment. The arrow shows that the largest punctate lesion (although coalesce) is 5 mm. Diameter of single lesions are no larger than 3 mm. Contiguous lesions were seen on T2w images which corresponded to ‘salt and pepper’/speckled appearance on the post-gadolinium MRI. Do note that the area involved on T2 do not exceed the post-gadolinium area of lesions and they are located peri-vascularly and can extend juxtacortically or caudally. (C) MRI brain axial post-gadolinium 6 weeks post-treatment showed complete resolution of the lesions.

As the patient fulfilled the clinical and radiological diagnostic criteria, he was treated for probable CLIPPERS. He was given intravenous methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg/day) for 5 days followed by oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks and then a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day for 1 month. His symptoms started to show marked improvement upon completion of intravenous steroid treatment. A repeated brain MRI 6 weeks post-treatment showed that the lesions had completely resolved (Fig. 1C). He was gradually weaned from oral steroid therapy over the next 4 months (the total course of oral steroids was nearly 6 months). He remained well at 19 months post-diagnosis with no recurrence clinically and radiologically. He was screened for fHLH, and the genetic panel for immunodeficiency was negative for known fHLH gene mutations. Serum ferritin, triglyceride, lactate dehydrogenase, and fibrinogen levels were normal, as was the full blood profile. However, heterozygous gene mutations corresponding to variants of uncertain significance were identified for LRRC8A exon 3, c.2023G>A (p.Glu675Lys); STK4 exon 7, c.823C>G (p.Leu275Val); and TNFRSF9 exon 8, c.626G>A (p.Arg209His).

CLIPPERS is a new and rare entity that was first described recently in 2010 [1,2]. It has been predominantly reported among adults, with about 80% of cases having only mild disabilities (modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or less) [1,2,4]. This differs significantly compared to pediatric cases [3-9]. The exact mechanism of CLIPPERS is still unclear. Proposed hypotheses include a possible pre-stage of a malignancy or an atypical presentation of well-characterised neuro-inflammatory diseases such as anti-myelin oligodendrocyte antibody disease [2]. From our observations, as there is a strong association with fHLH (classified as an inborn error of immunity) and T-cell predominance on histopathology, mechanisms related to immune dysregulation need to be considered.

According to our literature review, there is slight male preponderance, with the age of onset from 18 months to 16 years old. Most cases reported had symptoms for more than 1 month (except for patients 1 and 4) (Table 1) [3-10]. There were no specific CSF biomarkers for diagnosis. When describing brain MRI findings, five reported cases mentioned the presence of typical punctate and nodular lesions (patients 1, 2, 3, 8, and 10), but no previous reports stated the size of the largest punctate lesion in the reports, making a direct comparison of cases challenging.

With regards to treatment, all cases—either newly diagnosed or relapsed—were pulsed with intravenous methylprednisolone, followed by oral steroids. In the pediatric cohort, steroids were maintained for a shorter period (ranging from 3 to 6 months) due to concerns of other diseases, than in adults (more than 6 months). Among those who continued to have “true” CLIPPERS on re-evaluation at relapse, the second-line steroid-sparing agents used were varied and usually were a combination of oral and intravenous administrations [3-6, 10]. Although our case is currently in remission clinically and radiologically without steroids, this could be a “honeymoon” period and careful monitoring is required, as relapse or conversion to a non-CLIPPERS diagnosis can occur at any time post-diagnosis [2].

To date, outcomes among children appear less favourable than those among adults, as only 27.3% (3/11) of cases, including ours, recovered completely with no significant disabilities [6,10]. Eighteen percent (2/11) died due to treatment-related complications [3], 18% (2/11) had relapsing disease with severe disabilities [4,5], and 36.6% had alternative diagnoses on relapse (either lymphoma or fHLH) [3,7-9].

In summary, we would like to highlight some points relevant to pediatric CLIPPERS. Firstly, lesions on post-gadolinium imaging with a size that is equal or more than 9 mm are likely to be non-CLIPPERS cases, as highlighted in the revised criteria by Taieb et al. [2] or may have a poorer prognosis as observed in our literature review. Secondly, all pediatric CLIPPERS patients should undergo genetic testing for inborn errors of immunity at either the first diagnosis or relapse (specifically for fHLH). Thirdly, surveillance contrast brain MRI is recommended at least 6 months or earlier (if there is any clinical recurrence) in the first 2 years post-diagnosis, due to the high conversion rate to non-CLIPPERS diagnoses within this period. Finally, the genetic mutations detected in this patient should be kept for reference as they may prove significant for future research related to CLIPPERS.

Written informed consent to publish was obtained from the patient (IRB approval no.: NMRR ID-22-00026-ZFD [IIR]).

Notes

Teik Beng Khoo is an editorial board member of the journal, but he was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: VWML. Writing-original draft: VWML. Writing-review & editing: TBK, CZBCD, and KBAL.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article.