Once-Daily Extended-Release Levetiracetam Improves Medication Compliance in Adolescent Epilepsy Patients

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Since pharmacologic agents are the mainstay of epilepsy treatment, drug compliance is one of the most important factors in seizure control. Once-daily levetiracetam (LEV) has been proven to have the same efficacy as that of an immediate-release (IR) formulation. A reduced number of doses may improve drug compliance and patient satisfaction. The aim of this study was to assess drug compliance and patient satisfaction when changing from IR to an extended-release (ER) formulation.

Methods

Adolescent patients diagnosed with epilepsy who were taking LEV from 2018 to 2020 were included in this study. Compliance charts were reviewed retrospectively. We compared the frequency of seizure occurrence with the frequency of skipping doses and adverse effects before and after changing formulations. Changes in subjective compliance and satisfaction were also investigated.

Results

Among 585 patients taking LEV, 44 were included in this study. The average age of the included patients was 16.4±2.0 years. There was no significant change in the average seizure frequency (P=0.491) after switching formulations. Objective compliance based on chart records significantly improved after switching formulations (P=0.021). Additionally, 26 of 44 patients mentioned how they felt about switching formulations, of whom 25 (96.2%) were satisfied with the ER formulation. Thirteen of 24 patients (54.2%) reported better compliance.

Conclusion

Our study shows that the efficacy of LEV ER was similar to that of the IR formulation. The reduced number of medication doses improved patient satisfaction and medication compliance. LEV ER may be preferable in adolescent epilepsy patients.

Introduction

Since pharmacologic agents are the mainstay of epilepsy treatment, drug compliance is one of the most important factors in seizure control. Outcomes of missing antiepileptic drug (AED) can be associated with higher seizure frequency, increased likelihood hospital admission, epilepsy-related mortality, and higher cost of healthcare [1,2]. Some factors influencing compliance in epilepsy patients are age, understanding importance of taking medication, fear of side effects, feelings of stigma, and number of drugs [3]. Dosing frequency can also affect drug compliance [4-6]. Cramer et al. [7] reported patients having seizures after missed doses were associated with the frequency of seizure medication doses (P=0.04) and the number of seizure medication tablets/capsules (P=0.01).

Levetiracetam (LEV) has been widely used in the treatment of epilepsy because of its broad-spectrum efficacy, unique mechanism of action, and fewer adverse effects [8-10]. Extended-release (ER) LEV has been proven to have the same efficacy as that of an immediate-release (IR) formulation [11]. A pharmacokinetic study also showed that LEV ER was bioequivalent to LEV IR [12]. Several studies reported that LEV ER was effective for treating focal seizures [13,14]. The safety and adverse effect profile is also tolerable [15]. Previous studies showed that children and adolescents are more likely to have poor drug compliance [16], and a reduced number of doses may improve drug compliance and satisfaction in adolescent patients. However, there is no study exploring how LEV ER affects medication compliance. The aim of this study was to assess drug compliance and patient satisfaction after changing medication formulations from IR to ER.

Materials and Methods

1. Subjects

Subjects who visited the Department of Pediatrics at Chungnam National University Hospital, were diagnosed with epilepsy, and had switched formulation LEV IR to ER between 2018 and 2020 were enrolled in the study. Epilepsy was diagnosed according to the clinical definition of the International League Against Epilepsy as follows: (1) at least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring >24 hours apart; (2) one unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years; and (3) diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome [17]. Among 62 patients who fit the inclusion criteria, 18 patients were excluded. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) older than 20 years of age; (2) less than one month using LEV medication (either IR and ER each); and (3) the addition or removal of other medication duration the transition time (Fig. 1).

2. Method

We reviewed medical records retrospectively. Clinical characteristics of patients, such as age, sex, epilepsy type, frequency of seizure and missing dose, dose of LEV, number of AED, etiology of epilepsy, and comorbidities were included. We defined transition time as 3 months before and after changing formulation, compared the frequency of seizure occurrence with the frequency of skipping medicine before and after switching. And we reviewed occurrence of adverse events after switching formulation. All the patients who had seizure without any provocative factors such as fever, sleep deprivation and drug omit were received escalated dose of 250 mg of LEV during both periods. Additionally, alterations in subjective compliance and satisfaction were investigated.

3. Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). We compared the seizure frequency and compliance between prior to changing formulation and after changing formulation, analyzed the data, and considered P values <0.05 as significant for all comparisons and analysis. Since two of the enrolled patients had insufficient time of 3 months of IR and ER medication duration, these patients were excluded from comparison.

4. Ethics

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chungnam National University Hospital (CNUHIRB 2020-04-173). Due to its retrospective nature, the study was exempt from requiring informed consent from the participants.

Results

1. Clinical characteristics

A total of 44 patients were enrolled in this study. The average age of the included patients was 16.4±2.0 years (range, 13 to 20), and 22 were males (50%). Out of the 44 patients, 30 patients (68.2%) had focal epilepsy and 14 (31.8%) had generalized epilepsy. The average dose of LEV was 1,068.2±382.6 mg (range, 500 to 2,000). The duration of patients taking LEV medication before switching formulation was 827.2±852.2 days (range, 42 to 3,678). Most of the patients (84.1%) were on LEV monotherapy. Six out of 44 patients (13.6%) were taking two AEDs and one patient (2.3%) was taking three AEDs. The majority of patients had no comorbidities (68.2%) and had epilepsy with an unknown etiology (79.5%). Out of the 44 patients, four (9.2%) had adverse effects, such as drowsiness and dyspepsia. Among the four with adverse effects, two patients had serious adverse events of suicidal ideas and visual hallucinations. All the adverse events, except suicidal idea was occurred within 3 months of LEV ER period. Suicidal idea was occurred about 1 year after switching formulation. They were switched back to the previous formulation and their status returned to normal (Table 1).

2. Comparison of seizure frequency and compliance

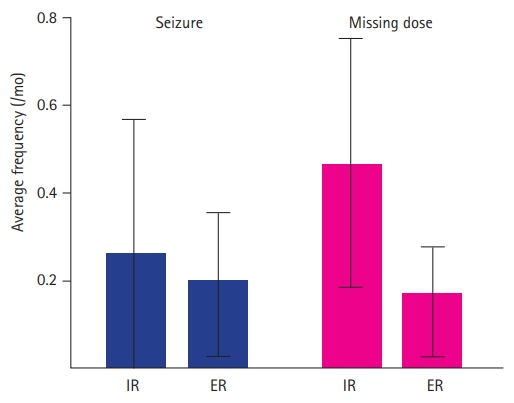

The average seizure frequencies during the period of IR and ER medications were 0.24±0.73 and 0.19±0.49 times per month, respectively. Twenty-two of 42 patients (52.4%) were seizure-free during the transition time. There was no significant difference in the average seizure frequency (P=0.491) before and after switching the formulation. A total of six seizures were related with missing a dose, which were excluded from this comparison. Average missing doses during IR and ER were 0.46±0.90 and 0.15±0.39 times per month, respectively. Twenty-four of 42 patients (57.1%) never missed a dose during the transition time. Compliance was significantly improved after switching formulation from IR to ER (P=0.021) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Average frequency of seizures and skipping medication during the 3 months before and after switching formulations. There was no significant difference in seizure frequency (P=0.491), but there was a significant difference in compliance (P=0.021). IR, immediate-releasing formulation; ER, extended-release formulation.

3. Difference of seizure frequency and compliance according to clinical characteristics

Differences in seizure frequency did not depend on sex, age, drug dose, epilepsy type, number of AEDs, IR duration, or presence of comorbidity. Enhancement of compliance was more prominent in the patients with older age (P=0.047), generalized epilepsy (P=0.027), higher dose (P=0.041), and longer IR duration (P=0.034), especially in patients without any comorbidities (P=0.009) (Table 3).

4. Subjective compliance and satisfaction

Twenty-six of 44 patients disclosed how they felt about switching. Thirteen of 24 patients (54.2%) expressed better compliance, and 25 (96.2%) of 26 patients were satisfied with the ER formulation (Table 4). The most common reason for missing a dose was forgetfulness (13 of 13, 100%).

Discussion

Since phenytoin ER was introduced to the market in 1976, many other AED ERs, such as carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, valproate, lamotrigine, and LEV, have been marketed and used widely [10]. ER formulations have potential advantages compared to IR drugs. They may have a higher compliance, better efficacy, less adverse events, and, as a consequence, reduced healthcare costs [18]. Higher compliance might be achieved by reducing dosing frequency. In a meta-analysis of results from six studies, once-daily dosing had significantly better compliance than more than once-daily dosing (odds ratio, 3.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.73 to 7.08; P<0.001) [4]. This is also true for epilepsy patients. Doughty et al. [19] found that switching from valproate IR to ER results in improvement of compliance, reduction of seizure frequency, and less reported adverse effects. Similar results were reported in patients taking carbamazepine ER [20]. Regarding LEV ER, Wu et al. [11] reported significant improvements in quality of life by using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions questionnaire. Our study showed significant improvements (P=0.021) in compliance when patients were taking LEV ER medication, which is compatible with previous studies. Additionally, we investigated how patients felt about switching, and most patients were satisfied with LEV ER. However, about half of the patients felt their compliance was unchanged. This may be due to the considerable number of patients (10 of 24, 41.7%) who did not miss doses prior to switching formulations. Higher satisfaction may lead to better compliance.

Enhanced control of seizures and less adverse effect can be achieved by a relatively stable concentration of ER drugs. Serum concentrations of IR drugs have more frequent peaks and troughs, where peaks are associated with adverse events and troughs are associated with seizures, especially in patients having a lower seizure threshold [21]. In addition to the above-mentioned reports, previous studies showed that oxcarbazepine ER had a better tolerability and lamotrigine ER had a better efficacy than IR formulation [22,23]. Currently, there is no evidence that LEV ER is more effective in seizure control than IR. In one placebo-controlled trial using indirect comparisons and meta-analytic techniques, LEV ER had significantly lower rates of treatment-emergent adverse events in the nervous system, psychiatric disorders, and metabolic and nutritional disorders than IR [24]. Our study showed a lower average seizure frequency during the ER period than the IR period, but it was not statistically significant. As most of the included patients were taking LEV IR for a long time without complications, we cannot compare the probability of adverse events between IR and ER. However, LEV ER could be associated with following adverse events. Two patients had dyspepsia and dizziness, which were tolerable and became normal as medication compliance continued. Two other patients had serious psychiatric adverse events, which were suicidal ideations and visual hallucinations, respectively. Both patients had been taking LEV IR over 5 months, and we could not evaluate serum concentrations of LEV at the time of the adverse events. It is unclear if LEV ER was the causative agent; however, it cannot be overlooked, since LEV is commonly associated with behavioral adverse effects, such as depression, hostility, and anxiety [15]. Many studies showed that ER drug has better tolerability than IR drug [25]. However, they also showed that many patients reported adverse events in the ER period, although less frequently than IR period [26-28]. Short-term follow-up and careful monitoring may be needed during the transition time. Although pharmacokinetic profiles of LEV ER are similar to IR, IR medication still leads to more peaks and troughs of serum concentration than ER-like drugs [12]. It may be possible to enhance our understanding of the efficacy of switching patients from LEV IR to LEV ER by performing larger-scale long-term follow-up studies.

It has previously been believed that there is a higher probability of seizures when patients missed an ER drug that is 100% of the entire day’s dose, instead of 50% in a twice-daily dose with an IR drug [29]. However, in a pharmacokinetic simulation study of serum drug concentrations following dosing irregularities with topiramate IR and ER, serum trough levels were only slightly lower for the ER drug when comparing missed doses [30]. In our study, missing dose-related seizures were four of 39 seizures in the IR period and two of 29 in the ER period. Although these data were not statistically evaluated, more missing dose-related seizures occurred in the IR period.

To our knowledge, this is the first study directly comparing LEV IR and ER from the aspect of compliance. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in seizure frequency, which was independent of other clinical characteristics, especially seizure type. The results of our study suggested that LEV ER is a better choice than IR, especially in patients with poor compliance.

Our study had some limitations. First, since this is a retrospective study, it was possible to omit events if the patient did not report them at that time. In particular, some patients might want to hide incorrect behavior, such as skipping medicine. However, similar to other epilepsy clinics, our clinic routinely check compliance, seizure occurrence, and adverse events. Second, many enrolled subjects were relatively well-controlled for seizures. There might be a selection bias toward patients having a higher seizure threshold. These patients were less likely to be affected by the trough level of serum drug concentration. This could be one reason for the results of similar efficacy between IR and ER. Furthermore, improved compliance was not led to better efficacy. These patients may be less affected by improved compliance in 3 months which was relatively short time. Third, because this study is from a single center and it is a small-scale study, the statistical power is limited.

Our study shows that LEV ER has an efficacy similar to that of IR formulations. The reduced number of medication doses improved patient satisfaction and medication compliance. ER drugs may have other advantages over IR, such as higher efficacy and tolerability. LEV ER may be the better option for adolescent epilepsy patients, especially those who have poor medication compliance.

Notes

Joon Won Kang is an editorial board member of the journal, but he was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: JWK. Data curation: SYJ. Formal analysis: SYJ. Funding acquisition: JWK. Methodology: JWK. Project administration: JWK. Visualization: YYY. Writing-original draft: SYJ. Writing-review & editing: YYY and JWK.

Acknowledgements

This work was presented at the Korean Epilepsy Congress in 2020.