Cranial Bruits Associated with Internal Carotid Artery Stenosis Due to Focal Arterial Dissection in an Infant

Article information

Head and neck bruits are well known findings in diagnostics. A cranial bruit can also cause one to sense a thrill; thus, self-diagnosis is possible in adults or in severe cases among pediatric patients. However, it is very hard to detect a cranial bruit in infants or young children, because it can only be diagnosed using a stethoscope. A bruit is caused by turbulence in intracranial or extracranial vessels and is mostly associated with the systolic phase. Innocent cranial bruits can be heard in a high cardiac output situation, but sudden onset of cervical bruits, particularly bruits during the systolic phase or detected throughout the entire head and neck including both eyeballs, must be considered to indicate life-threatening conditions such as carotid artery stenosis, an arteriovenous fistula, and an intracranial hemangioma [1,2].

A 7-month-old boy was admitted to our hospital because of the sudden onset of an audible rhythmic sound in the occipital area 1 week ago, which was detected by his mother. He was born at full term by uncomplicated delivery. Before admission, he had been healthy and had normal neurodevelopment. He had neither other symptoms nor a history of trauma. Family history showed nothing particular, except for subarachnoid hemorrhage in his grandmother.

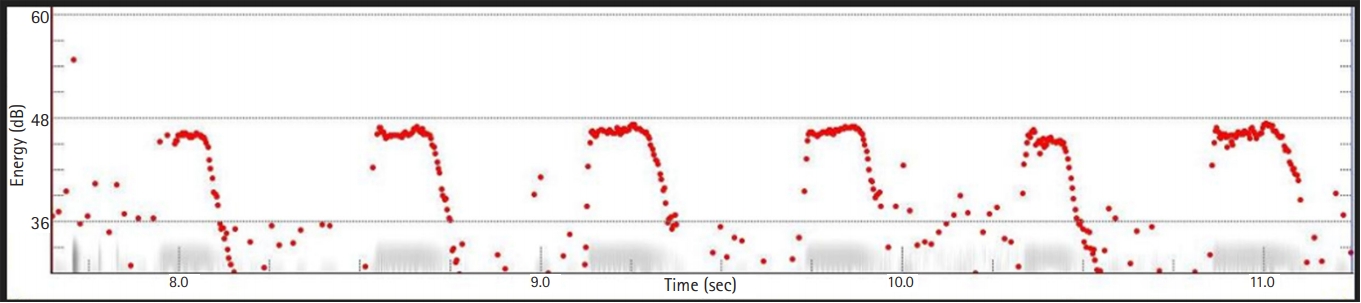

Upon physical examination, his vital signs were as follows: heart rate, 136 beats per minute; blood pressure, 94/66 mm Hg; body temperature, 36.8°C; and respiration rate, 34 breaths per minute. He showed regular heartbeats without any murmur. However, systolic bruits were detected across the entire scalp, particularly in the left posterior auricular area, but thrills were not detected. After recording with an electronic stethoscope (3M™ Littmann® Electronic Stethoscope Model 3200, 3M, St. Paul, MN, USA), acoustic analysis using a Computerized Speech Lab (CSL™, CSL models 4500, KayPENTAX, Montvale, NJ, USA), confirmed that the bruits matched the heartbeats (Fig. 1). His mental status was alert without any abnormalities in cranial nerve function tests. Motor power showed grade 5 in all extremities, tone was normal, and deep tendon reflexes were normal. No pathologic reflexes were present.

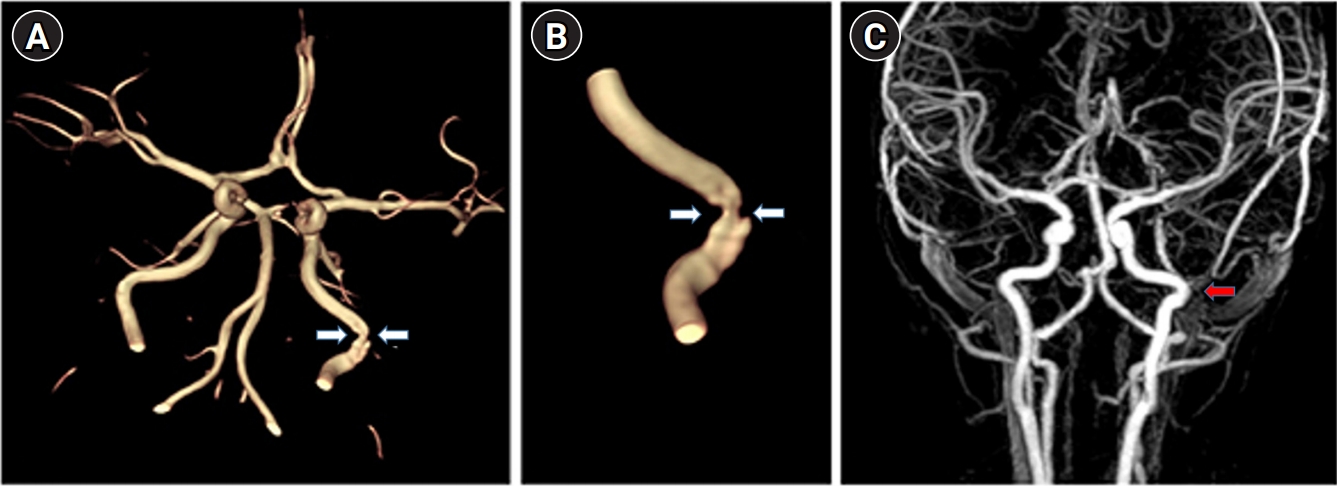

There was no specific finding in routine laboratory investigations, including bleeding tendency, blood glucose level, and lipid profile. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not show any definite intracranial lesions. However, brain magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed arterial stenosis at the left internal carotid artery that may have been due to focal arterial dissection (Fig. 2A and B). Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography (TCD) showed that the peak blood flow velocity of the left internal carotid artery was 109 cm/sec and that of the right internal carotid artery was 91.5 cm/sec, but TCD did not show any stenotic lesions. Electroencephalography (EEG) showed normal symmetric background activities for his age, and interictal brain perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) showed symmetric perfusion in brain parenchyma.

(A, B) Brain magnetic resonance imaging shows focal stenosis of the left internal carotid artery (white arrows). (C) Follow-up brain magnetic resonance angiography reveal a completely improvement the stenotic lesion after 8 months (red arrow).

Previous reports suggest that if the internal carotid artery shows a peak blood flow velocity of 125 cm/sec or higher, it can be said that the internal carotid artery has more than 50% stenosis in an adult [3,4]. They recommended antiplatelet treatment in such a situation [3,4].

His vital signs were stable, and he had no remarkable neurological abnormalities. His peak blood flow velocity of the left internal carotid artery was less than 125 cm/sec. Therefore, we recommended observation and a follow-up brain MRA without any medication or intervention, as previous reports have recommended observation in a similar situation [3-5].

After about 5 months of follow-up, the bruits gradually started to decrease, and after 7 months of follow-up, no more bruits could be heard using a stethoscope. Follow-up brain MRA, which was conducted at around 8 months after the initial MRA, confirmed that the previously seen vascular lesion had fully recovered (Fig. 2C).

We reported a case of a 7-month-old boy visiting our hospital for an abnormal sound in the occipital area. Brain MRA showed partial stenosis of the left internal carotid artery that may have been caused by focal dissection. Brain MRI, EEG, TCD, and brain SPECT were performed to evaluate brain function, and they showed no specific findings. At follow-up after 8 months, the stenotic lesion and bruits had improved without any medication or intervention. During follow-up observations, this patient showed suitable development for his age, without any abnormalities.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jeonbuk National University Hospital (IRB No: 2020-07-029). Informed consent was waived by the board.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: SJK, KUC. Data curation: KUC and SJK. Formal analysis: KUC and SJK. Methodology: KUC and SJK. Project administration: KUC and SJK. Visualization: KUC and SJK. Writing-original draft: KUC and SJK. Writing-review & editing: KUC and SJK.