|

|

- Search

| Ann Child Neurol > Volume 29(4); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of occipital nerve block (ONB) in pediatric patients with headache in the occipital region.

Methods

Among 302 patients who visited our headache clinic during a 2-year period, we retrospectively reviewed the charts of 26 patients who complained of primary headache in the occipital region, and divided them into two groups according to the main treatment: ONB or oral drug treatment (ODT).

Results

The mean age of the 26 patients was 11.7±3.2 years. No statistically significant differences were found between the ONB and ODT groups in age, sex, sites of pain, duration of having experienced symptoms, and the duration, frequency, and severity of episodes (P>0.05). There was no statistically significant difference in remission between the ONB and ODT groups. However, in the ONB group, the time taken to achieve remission was significantly shorter than in the ODT group (P<0.05). Additionally, in the ONB group, the duration of medication and the period of outpatient treatment were significantly shorter than in the ODT group (P<0.05).

Headache is a common disease in children and adolescents, with 29.1% of school-age children in South Korea complaining of headaches [1]. Pediatric headaches can be diagnosed as primary or secondary headaches according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3), and the treatment of categorized headaches has been partially established [2,3]. However, in clinical practice, there are some patients with primary headaches that are difficult to diagnose, such as short-lasting headache (SLH) or headaches in the occipital region [4-9]. Most of these patients have severe symptoms and need rapid and appropriate treatment [5]. In recent years, occipital nerve block (ONB) has been rarely applied as a treatment for these headache patients. ONB is being tried in pediatric patients with chronic migraine, aggravated migraine, new daily persistent headaches (NDPH), post-traumatic headache, occipital neuralgia, SLH, and psychiatric disorders [10-12].

To study the effect of ONB in children suffering from primary headache in the occipital region, we compared patients who received ONB and those who did not.

We retrospectively reviewed the charts of 26 (8.61%) patients who complained of occipital pain among 302 patients who visited the headache clinic at Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine between July 2016 and August 2018. Headaches were diagnosed according to the ICHD-3 system [2]. These 26 patients had poorly responded to acute treatment involving simple analgesics or intravenous non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. For all patients, a physical examination including tender points and limitations of neck motion was performed. Imaging studies (brain magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], cervical spine X-rays, etc.) and screening behavioral and psychiatric tests such as the Korean Child Behavior Checklist (K-CBCL), Kovacs' Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), State Anxiety Inventory for Children (SAIC), and the Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (TAIC) were done. Headaches due to structural abnormalities in the brain or neck and psychiatric disorders were excluded, as follows: (1) headaches due to abnormalities on brain MRI (n=7, 2.3%); (2) headaches due to cervical spine lordosis (n=70, 23.2%); and (3) headaches due to psychiatric disorders (n=10, 3.3%).

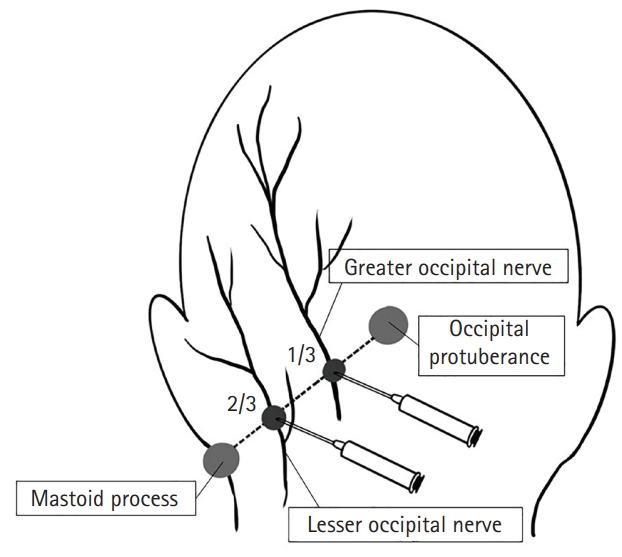

The patients were divided into ONB and oral drug treatment (ODT) groups according to the main treatments. We performed ONBs using landmark-based injections along the nerve pathway of the greater and lesser occipital nerves (Fig. 1). Occipital protuberance and mastoid processes were used as landmarks. We injected a total of 40 mg of methylprednisolone (MPD) and 20 mg of 2% lidocaine in four divided doses under 40 kg of body weight (80 mg of MPD and 40 mg of 2% lidocaine above 40 kg) [8,10,12,13].

Given the lack of specific treatment guidelines for unspecified headaches [14], the ODT group received empirical treatment for primary pediatric headache, including amitriptyline or topiramate [14-18]. Remission was defined as a decrease in the frequency of headache attacks by ≤75% [19].

To compare the effects of treatment between the two groups, the remission, time to reach remission, duration of medication, and period of outpatient treatment were evaluated. For statistical analysis, the independent-sample t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare the two groups using SPSS version 27 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review of Board of the Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital (HKS 2021-03-038). Due to its retrospective nature, the study was exempt from requiring informed consent from the participants.

The mean age of 26 patients with primary occipital pain with headaches was 11.7±3.2 years, and the male-to-female ratio was 1:1.4 (Table 1). Among 26 patients, 19% (n=5) had unspecified occipital headache, 35% (n=9) had aggravated migraine, 27% (n=7) had SLH, and 19% (n=5) had NDPH (Table 2).

Throbbing pain was the most commonly reported pain type, and the frequency was 5.2±3.0 headaches per week. The headache severity score was 5.9±1.7 on a visual analog scale, and patients had experienced symptoms for periods of time ranging from 3 days to 120 months (Table 1).

No significant differences in age, sex, and sites of pain were observed between groups A and B (Table 1). In group A, the ratio of the throbbing type to the pressure type was 7:6; however, in group B, the ratio of the throbbing type to the pressure type was 11:2, which was a statistically significant difference (P<0.05). Additionally, no significant difference was observed in the duration of having experienced symptoms, duration of episodes, frequency, and severity between the two groups (P>0.05).

In a comparison of the therapeutic effects between groups A and B, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of patients with headache remission between groups A and B (P>0.05). However, the time until remission in group A was significantly shorter than that in group B (P<0.05) (Table 3). Significantly fewer drugs were used in group A than in group B (P<0.05). Group A had a significantly shorter duration of medication use (P<0.05), significantly fewer outpatient visits for treatment (P<0.05), and a significantly shorter period of outpatient visits for treatment (P<0.05).

Headache is a highly common disease among children and adolescents and substantially affects their quality of life [20]. In a study of school-aged children in South Korea, 29.1% of children developed headaches, and approximately 6.7% reported experiencing other types of headache than migraine and tension-type headaches [1]. Children with headaches frequently visit the emergency room, and approximately 14% of them have unspecified headache symptoms, which are classified as other headaches [21]. However, the category of other headaches in children is not well classified, and these cases are often diagnosed as SLH, occipital headache, or NDPH [1,5,22].

Involvement of the occipital region in other headaches occurs in approximately 25.9% to 52.9% of SLH cases [4,7], 60% of NDPH cases [12], 10.8% of aggravated migraines, and approximately 12.4% of pediatric headaches observed in the emergency room [5]. In our study, approximately 8.6% of the 302 patients developed headaches in the occipital region.

Patients with SLH often develop severe headaches [4], and in a South Korean study [7], 85.1% of them complained of moderate to severe headaches. Additionally, headaches in the occipital region require rapid treatment; however, there are no specific treatment guidelines [14]. As empirical drug treatment, analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are administered at the beginning of the acute phase and prophylactic drugs such as amitriptyline and topiramate for about 3 to 12 months, followed by a gradual reduction of the prophylactic drugs [15-18]. In our study, the oral medications were planned for at least 3 months. Four patients were excluded; one patient self-interrupted medication and three patients discontinued outpatient visits.

A few recent reports have investigated the effectiveness of ONB for pediatric headaches [11,12]. Anatomically, the occipital nerves originate from the nerve roots of the second cervical spinal nerve (C2). Through the sensory branches of these nerves, a stimulus is transmitted to the trigeminal nucleus caudalis, where pain signals are transmitted upward, causing a headache. ONB reduces headaches by blocking afferent stimulation of the trigeminal nucleus caudalis [23-25].

In ONB, the injection site is the point where the greater and lesser occipital nerves pass through the line connecting the occipital protuberance and mastoid process [10,12]. The ONB injection can be done manually or under ultrasound guidance [26]. In our study, MPD and 2% lidocaine were injected into four sites on both sides using the occipital protuberance and mastoid process as landmarks. In one patient, an additional injection was performed at the maximally tender point of the temporal area of the head.

The side effects of ONB were mild in two patients in our study; local bleeding, pain in the injected site. Local bleeding was transient, and the duration of pain was less than 24 hours. Minor side effects (8.2%) have also been described in other reports, such as mild aggravation of headache and pain at the injection site [12]. In the ODT group, one patient (7.7%) complained of nausea and another three patients (23.1%) experienced headache aggravation. There was no statistically significant difference in side effects between the ONB group and the ODT group (Table 3).

ONB was effective in 68% of patients with migraines and 59% with NDPH [9], and the headache frequency was reduced by more than half in 41% of patients with migraines [11]. In our study, there was no statistically significant difference in remission between groups A and B. In group A, the time until remission was significantly shorter than that in group B (P<0.05) (Table 3). Group A also had a significantly shorter duration of medication and period of outpatient treatment than group B. This suggests that ONB is more effective than ODT in reducing the time until remission and treatment period. Therefore, it is considered worthwhile to attempt ONB for rapid treatment and shortening of the treatment period in patients with unspecified headaches, particularly headaches involving occipital pain.

The limitations of our study are the insufficient number of patients who received ONB therapy and the possibility of inaccuracies in the data because children have difficulties describing headache.

In our study, ONB reduced the time until remission and the treatment period. Therefore, it is necessary to consider ONB as well as ODT for pediatric occipital headaches. Future prospective studies on ONB should include a sufficient number of patients, as well as patients with chronic headache.

Notes

Author contribution

Conceptualization: HJS and KHL. Data curation: HJS and KHL. Formal analysis: HJS and KHL. Methodology: HJS and KHL. Project administration: HJS and KHL. Visualization: HJS. Writing-original draft: HJS and KHL. Writing-review & editing: HJS and KHL.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of the occipital nerve block (A) and oral drug treatment (B) groups

Table 2.

Comparison of the diagnoses in the occipital nerve block (A) and oral drug treatment (B) groups

| Diagnosis | Group A (n=13) | Group B (n=13) |

|---|---|---|

| Unspecified occipital headache | 4 | 1 |

| Migraine (aggravated) | 6 | 3 |

| Short-lasting headache | 1 | 6 |

| New daily persistent headache | 2 | 3 |

Table 3.

Comparison of the effects of treatment in the occipital nerve block (A) and oral drug treatment (B) groups

References

1. Rho YI, Chung HJ, Lee KH, Eun BL, Eun SH, Nam SO, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of primary headaches among school children in South Korea: a nationwide survey. Headache 2012;52:592-9.

2. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38:1-211.

4. Vieira JP, Salgueiro AB, Alfaro M. Short-lasting headaches in children. Cephalalgia 2006;26:1220-4.

5. Genizi J, Khourieh-Matar A, Assaf N, Chistyakov I, Srugo I. Occipital headaches in children: are they a red flag? J Child Neurol 2017;32:942-6.

7. Baek JW, Shim YS, Kim SK, Lee KH. Short-lasting headache in children. Korean J Headache 2011;12:61-7.

10. Dubrovsky AS. Nerve blocks in pediatric and adolescent headache disorders. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2017;21:50.

11. Szperka CL, Gelfand AA, Hershey AD. Patterns of use of peripheral nerve blocks and trigger point injections for pediatric headache: results of a survey of the American Headache Society Pediatric and Adolescent Section. Headache 2016;56:1597-607.

12. Puledda F, Goadsby PJ, Prabhakar P. Treatment of disabling headache with greater occipital nerve injections in a large population of childhood and adolescent patients: a service evaluation. J Headache Pain 2018;19:5.

13. Gelfand AA, Reider AC, Goadsby PJ. Outcomes of greater occipital nerve injections in pediatric patients with chronic primary headache disorders. Pediatr Neurol 2014;50:135-9.

14. Korean Neurological Association; Korean Headache Society. Guidelines for management of migraine. 2nd ed. Seoul: KNA; 2008.

15. Lagrata S, Cheema S, Watkins L, Matharu M. Long-term outcomes of occipital nerve stimulation for new daily persistent headache with migrainous features. Neuromodulation 2021;24:1093-9.

18. Kacperski J, Hershey AD. Preventive drugs in childhood and adolescent migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2014;18:422.

19. Lee JH, Cho KL. A study on the therapeutic effects of Topiramate according to the types of migraine. Korean J Pediatr 2010;53:554-9.

20. Rho YI. Prevalence of headache and headache-related disability in children and adolescents. J Korean Med Assoc 2017;60:112-7.

21. Hong EY, Choi KY, Kim SK, Jung AY, Lee KH. Clinical characteristics and diagnosis for pediatric headache in the emergency department. Korean J Headache 2013;14:1-5.

22. McAbee GN, Morse AM, Assadi M. Pediatric aspects of headache classification in the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3 beta version). Curr Pain Headache Rep 2016;20:7.

23. Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, Hoffmann J, Schankin C, Akerman S. Pathophysiology of migraine: a disorder of sensory processing. Physiol Rev 2017;97:553-622.

24. Reed KL, Black SB, Banta CJ 2nd ed, Will KR. Combined occipital and supraorbital neurostimulation for the treatment of chronic migraine headaches: initial experience. Cephalalgia 2010;30:260-71.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- Scopus

- 2,645 View

- 107 Download

- Related articles in Ann Child Neurol

-

Risk Factors for Chronic Kidney Disease in Pediatric Patients with Epilepsy2021 January;29(1)

Recurrent Bacterial Meningitis in Pediatric Patients with Anatomical Defects.2011 August;19(2)